Dressler Syndrome on the Electrocardiogram

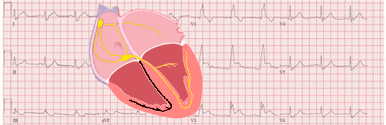

Dressler syndrome, also known as late infarct associated pericarditis, was described in 1956 by William Dressler.1 It is a form of secondary pericarditis with or without a pericardial effusion.2 3

It is a disease that typically occurs between two and eight weeks after an acute myocardial infarction.2 3

Dressler syndrome is part of the post-cardiac injury syndromes, which include: post-myocardial infarction pericarditis triggered by ischemic myocardial necrosis, post-pericardiotomy syndrome after surgical trauma, and post-traumatic pericarditis due to either iatrogenic or accidental injury.2 3

Late post-myocardial infarction pericarditis (Dressler syndrome) should be differentiated from early infarct-associated pericarditis, which occurs within five days after an acute myocardial infarction.

Epidemiology of Dressler Syndrome

Prior to the reperfusion era it had been reported with an incidence of 5%. Newer studies have reported that this condition is seen in much fewer patients.3 4

This reduction of incidence may be attributable to early reperfusion resulting in a reduction in the size of the infarct and subsequently damaged myocardium.

The effects of standard-of-care drugs, such as ACE inhibitors, some beta-blockers, statins, and aspirin, may also explain the reduced incidence of Dressler syndrome.

Predisposing Factors for Dressler Syndrome

Predisposing factors for Dressler syndrome include:3

- Larger myocardial infarction

- Viral infections

- Surgeries involving greater myocardial damage

- Younger age

- Prior history of pericarditis

- Prior treatment with prednisone

- B negative blood type

- Use of halothane anesthesia.

Signs and Symptoms of Dressler Syndrome

Dressler syndrome typically occurs two to eight weeks after STEMI. It is rare in the primary PCI era and is often related to late reperfusion or failed coronary reperfusion, as well as to larger infarct size 2 4.

Though not a common condition, Dressler syndrome should be considered in all patients presenting with persistent chest pain, malaise or fatigue following a myocardial infarction or cardiac surgery, especially if symptoms present greater than two weeks following the event 3 5.

Symptoms may be accompanied by fever and increased inflammatory biomarkers. In most cases, the pain is self-limited and responds to conservative measures 5.

On physical examination, patients with Dressler syndrome are often tachycardic with a pericardial friction rub heard on auscultation. Additionally, patients may present with pulsus paradoxicus 5.

Diagnostic Criteria of Dressler Syndrome

Diagnostic criteria of Dressler syndrome do not differ from those for acute pericarditis including two of the following criteria 2:

- Pleuritic chest pain (85–90% of cases)

- Pericardial friction rub (≤33% of cases)

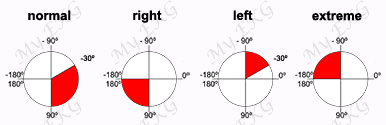

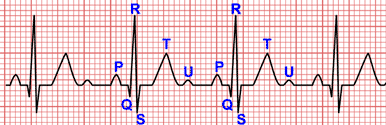

- ECG changes (≤60% of cases), with new widespread ST-segment elevation, usually mild and progressive, or PR segment depression in the acute phase

- Pericardial effusion (≤60% of cases and generally mild)

EKG Changes of Dressler Syndrome

ECG changes in Dressler syndrome are present in approximately 60% of patients 2.

ECG can provide evidence of typical alterations associated with pericarditis, such as recurrent or worsening widespread ST-segment elevation without early T wave inversion 2 3 5.

PR segment depressions in multiple leads may also be present 2 4.

Identification and interpretation of these findings is, however, often complicated by the underlying pathological condition which triggered the Dressler syndrome 4.

Electrical alternans and/or low voltage QRS complexes may also be observed if there is a large volume pericardial effusion 3.

Complications of Dressler syndrome

Importantly, and in marked contrast to early infarct-associated pericarditis, Dressler syndrome implies a relevant risk of recurrence 3.

Nevertheless, complications such as late cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis are rare for early infarct-associated pericarditis as well as for Dressler’s syndrome.

Tratment of Dressler Syndrome

Anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended in post-STEMI pericarditis as in post-cardiac injury pericardial syndromes for symptom relief and reduction of recurrences.

Aspirin is recommended as first choice of anti-inflammatory therapy post-STEMI at a dose of 500–1000 mg every 6–8 hours for 1–2 weeks, decreasing the total daily dose by 250–500 mg every 1–2 weeks 2 5.

Colchicine is recommended as first-line therapy as an adjunct to aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy for 3 months. It is also recommended for the recurrent forms (6 months) 2 5.

Corticosteroids are not recommended due to the risk of scar thinning with aneurysm development or rupture 2.

Although pericarditis is not an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, caution should be exercised because of the potential for hemorrhagic conversion 5.

Pericardiocentesis is rarely required, except for cases of haemodynamic compromise with signs of tamponade 2 5.

References

- 1. Dressler W. The Post-Myocardial-Infarction Syndrome. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1959; 103(1):28-42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1959.00270010034006.

- 2. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With ST-Segment Elevation: The Task Force for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2017; Aug 26. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393.

- 3. Leib AD, Foris LA et al. Dressler Syndrome [Internet]. statpearls [consulted Nov 7 2020]. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441988/.

- 4. Sasse T, Eriksson U. Post-cardiac injury syndrome: aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment. e-Journal of Cardiology Practice. 2017; 15(21). Available from: www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice.

- 5. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127: e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6.

If you Like it... Share it.