Clinical Features of Chest Pain

The leading symptom initiating the diagnostic and therapeutic cascade in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome is acute chest discomfort described as pain, pressure, tightness, and burning 1.

This is why it is important to perform a rapid and effective symptom evaluation for each patient with chest pain in order to recognize the characteristics of pain of dangerous etiology 2.

Although the evaluation of symptom severity usually focuses on the detection of suspected acute coronary syndrome, it should be noted that other diagnoses, such as aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism and pneumothorax, also need to be treated urgently 2.

Most episodes of chest pain, seen by a general practitioner, are caused by musculoskeletal problems and only about 20% are of cardiac origin 2.

The degree of symptoms is a poor indicator of the patient’s risk of having a serious condition.

The type of chest discomfort (pain), pattern of radiation and concomitant symptoms, such as nausea, sweating and cold, pale skin are valuable signs of a possible serious condition.

Anginal pain:

From 2010 NICE clinical guideline: chest pain of recent onset 4.

- Constricting discomfort in the front of the chest, or in the neck, shoulders, jaw, or arms

- Precipitated by physical exertion

- Relieved by rest or glyceryltrinitrate within about 5 minutes.

Three of the features above are defined as typical angina. Two of the three features above are defined as atypical angina. One or none of the features above are defined as non-anginal chest pain 4.

A patient who is haemodynamically unstable (shock, low blood pressure) or who displays an arrhythmia (severe bradycardia/tachycardia) needs immediate attention regardless of the underlying cause 2.

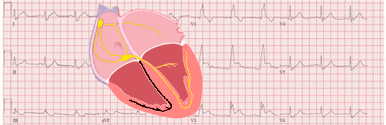

What to look for on the EKG of a patient with chest pain

Although the characteristics of chest pain can guide us, it is the combination of the clinical picture with the electrocardiogram that will allow us to diagnose serious conditions that require urgent action.

Comparison with previous tracings is valuable, particularly in patients with pre-existing EKG abnormalities 1.

In more than 30% of patients with an acute coronary syndrome, the EKG may be relatively normal or initially nondiagnostic; if this is the case, the EKG should be repeated (at 15 to 30 minute intervals during the first hour), especially if symptoms recur 3 5.

Severe Cardiac Arrhythmias

First, severe cardiac arrhythmias must be ruled out (ventricular tachycardias, supraventricular tachycardias, complete AV block, or extreme bradycardias).

The presence of any of these arrhythmias may lead to hemodynamic instability, and urgent measures should be taken.

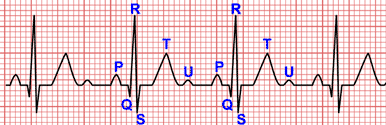

ST-Segment Elevation

In patients with suggestive signs and symptoms, the finding of persistent ST-segment elevation in at least 2 contiguous leads indicates STEMI, which mandates immediate reperfusion 1.

A prolonged new convex ST-segment elevation, particularly when associated with reciprocal ST-segment depression, usually reflects acute coronary occlusion and results in myocardial injury with necrosis 5.

Reciprocal changes can help to differentiate STEMI from acute pericarditis or early repolarization changes 5.

ST-Segment Depression and T-Wave Changes

Characteristic abnormalities of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome include ST-segment depression, transient ST-segment elevation, and T wave changes 1.

New horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression ≥0.05 mV in two contiguous leads and/or new T wave inversion ≥0.1 mV in two contiguous leads are suggestive of of acute myocardial ischaemia 5.

More profound ST-segment shifts or T wave inversions involving multiple leads are associated with a greater degree of myocardial ischaemia, and a worse prognosis 5.

ST-segment depression ≥1 mm in 8 or more leads associated with ST-segment elevation in lead aVR or in lead V1 is suggestive evidence of multivessel disease or left main disease 5.

Persistent ST-segment depression greater than 0.5 mm in leads from V1 to V3 may be indicative of true posterior myocardial infarction and should be treated in a similar way to STEMI patients 3.

ST-segment and T wave alterations may also be observed in left ventricular hypertrophy, bundle branch blocks, and ventricular pacing, which may mask signs of ischemia or injury 3.

Q wave

The development of new Q waves indicates myocardial necrosis, which starts minutes/hours after the myocardial insult.

Transient Q waves may be observed during an episode of acute ischemia or (rarely) during acute myocardial infarction with successful reperfusion 5.

The presence of pathologic Q waves increase the prognostic risk 5.

Left Bundle Branch Block

Patients with a high clinical suspicion of ongoing myocardial ischaemia and left bundle branch block should be managed in a similar way to STEMI patients, regardless of whether the left bundle branch block is previously known 1.

In contrast, haemodynamically stable patients presenting with chest pain and left bundle branch block only have a slightly higher risk of having myocardial infarction compared to patients without left bundle branch block 1.

The modified Sgarbossa criteria may be useful in the detection of candidates for immediate coronary angiography 1.

Right Bundle Branch Block

In patients with right bundle branch block, ST-segmente elevation is indicative of STEMI while ST-segment depression in leads I, aVL, and V5 - V6 is indicative of NSTE-ACS 1.

More than 50% of patients presenting with acute chest pain and right bundle branch block to the emergency department will ultimately be found to have a diagnosis other than myocardial infarction 1.

Normal EKG

A normal electrocardiogram does not exclude an acute coronary syndrome and occurs in 1% to 6% of patients with chest pain 3.

Acute coronary syndrome with a normal EKG may be associated with left circumflex or right coronary artery occlusions, which can be electrically silent.

If the standard leads are inconclusive and the patient has signs or symptoms suggestive of ongoing myocardial ischaemia, additional leads should be recorded 1.

In in these cases posterior leads (V7 to V9) or right-sided leads (V3R to V6R) may be helpful (read right-sided leads and posterior leads) 1 3.